Home Baked, with Love

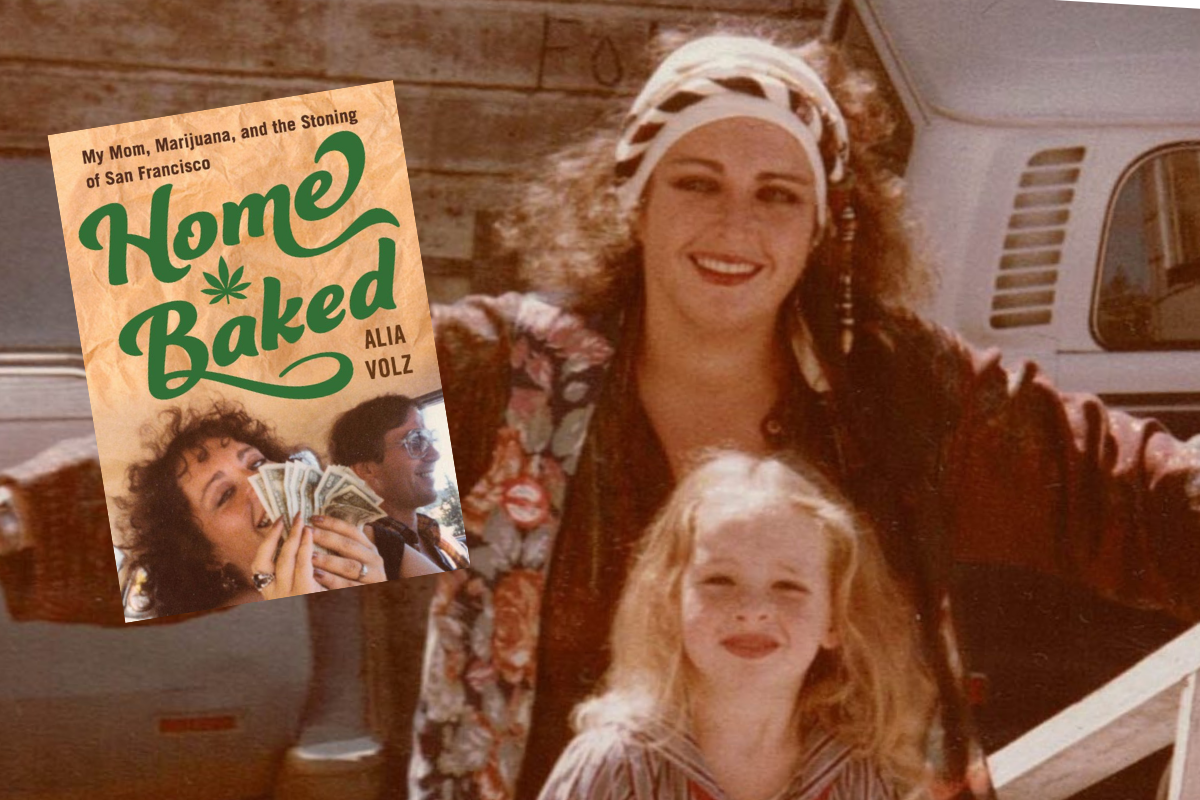

Alia Volz has mastered The Hybrid Memoir genre, and in fact, we know very little about her, considering its a memoir. Home Baked, My Mom, Marijuana and The Stoning of San Francisco is a first hand account of growing up as the daughter of the founder of the pot-brownie collective Sticky Fingers, Meridy Volz.

The reader learns about The Compassionate Use Act (prop 215 of 1996) and those responsible for it, the politics of the AIDS crisis and how healthcare and the still federally illegal substance that we now all take for granted as widely available in most states -marijuana and cannabis, in its myriad of forms – is nearly non-prosecutable, thanks to the author’s parents who were a pair of deeply passionate and eccentric artists. We do learn about Alia’s life, but is it through her eyes as an astute reporter of her mother’s life and legacy, which covers a lot of interesting ground. I found myself referencing the references frequently, and enjoying the recognition of the I was there moments like in Chapter One, Eat It Baby! where Meridy moves to San Francisco in the mid seventies: “…she couldn’t imagine ever wanting to leave…A peculiar darkness seemed to well up from within San Francisco, reminding Mer of a graceful image painted over an ugly one. In what was historically known as a wide-open town, excess could become poisonous and often did.”

Even though I didn’t move to The City until decades later, it is a right of passage to experience this darkness firsthand: every SF resident has more than one scary and harrowing-lost-in-the-city-story they are too ashamed or embarrassed to share.

Volz does a great job of weaving the intricacies of her father’s epilepsy and self medicating habits, her mother’s outlaw tendencies and her own awareness in the moment of what was quote unquote normal or allowed to discuss with outsiders. Afterall, consider that the D.A.R.E. to keep kids off drugs program was the backdrop for the author’s childhood. She knew at an early age her mother was not hocking girl scout cookies, and she was an adorable accomplice in an innocent yet clandestine farmer’s market cookie run for many Saturdays of her childhood.

Having some firsthand experience myself as a pot-cookie-maker and provider to the backstage artists and crew at Shoreline Amphitheatre in the early 2000s, I enjoyed the descriptions of the welcome arms and the anticipation of Meridy’s arrival at the markets.

The brownie lady is here, the brownie lady is here!

Much anticipated announcements – cries of joy – for Sticky Fingers deliveries at the markets

Alia describes the rush of selling out of all the stock and the amount of high production to meet ever-growing demand. My operation was always small, 3 or 4 dozen at the most, per show weekend. Sticky Fingers was operating for years, undetected by authorities, in much much higher volume.

Aside from the marijuana business and the legalities and politics of it, I marveled at how Volz captured the ever-churning nature of the gold rush spirit of San Francisco. In describing the Harvey Milk era and his assassination by Dan White, “the two quixotic crusaders – one representing old San Francisco values, the other rising from the new city – were on a collision course,” she could also be describing the current zeitgeist of The City, where the techies and the gentrification are constantly replacing the old with the new. When someone new moves in, someone must be displaced, it’s how this city has always worked.

The most telling glimpse into Alia’s current attitude is when she throws a little shade to those modern day techies for their collective amnesia as they vape openly in the courtyards of the high-tech company dominated gardens of downtown and hipster gulches of the mission district. She laments that there is no recognition of the balls it took for these ground-breakers to pave the way and allow for what we seem to be taking for granted. “Sticky Fingers Brownies began as a lark and grew through friendship, feminist badassery, and hippie magic.” That’s a combination that is special, and especially hard to recreate on the page, which I think Volz did very well. As a memoir writer myself, attempting a hybrid genre on the tech movement as I’ve witnessed it first hand from 1999-2019, I was also relieved to see that it took a decade of the author’s life to get this book out. It was definitely a decade well spent, and I highly recommend the book for anyone interested in how feminist badassery works.